Pathogenesis

The study of effects of viral infection on the host.

Pathogenecity

The sum total of the virus-encoded functions that contribute to virus propagation in the infected cell, in the host organism, and in the population.

- Depends on the genetic make up or genotype.

- Sum of cellular events, reactions and other pathologic mechanisms in the development of disease.

Virulence

The degree of pathogenecity as indicated by the severity of the disease produced and the ability to invade the tissues of the host.

- The competence of a virus to produce pathogenic effects.

The Interaction of Viruses and their Hosts

- Dynamic.

- Host evolves and develops mechanisms of defense against viruses.

- Host recently defends against viruses due to medical progress.

- Viruses respond by exploiting their naturally-occurring genetic variation to respond against host resistance.

Virus-Human Relationships

- Virulent viruses either kill their hosts or induce life-long immunity in the survivors. They can survive only where large, interacting host populations are available and exposed for their continued propagation.

- Virulent viruses (ex. smallpox, measles) could not have established in human populations until large, settled communities appeared.

- Less virulent viruses that entered into a more benign, long-term, permanent relationship with their hosts were more likely to be the first to become adapted to replication in the earliest human populations (retroviruses, herpesviruses, papillomaviruses).

- Some modern viruses were associated with the earliest precursors of mammals and co-evolved with humans. Others entered human populations recently.

- Some viruses that eventually established themselves in human populations were transmitted to early humans from animals, much as still happens today.

Viruses and Plants

- Viruses have destroyed a variety of crops in the last 12,000 to 14,000 years since agriculture started.

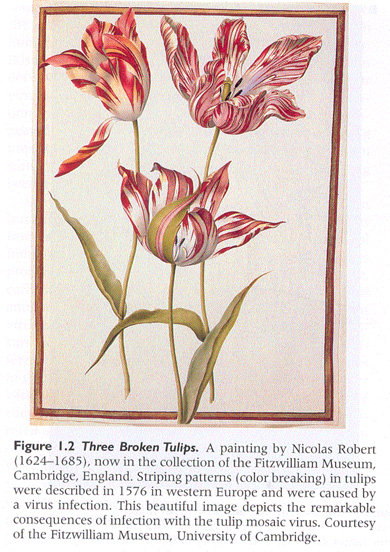

- Stripping patterns (color breaking) in tulip petals were described in 1576 in Holland and were caused by the tulip mosaic virus. Bulbs were extremely expensive.

- An example of a disease leading to severe economic disruption is the growing spread of cadang-cadang viroid in coconut palms in Oceania.

- Rice is constantly attacked by viral diseases.

- Barley yellow dwarf virus is a serious disease.

- 50 million citrus trees were lost to tristeza virus; and, 200 million cocoa trees were lost to the 'swollen shoot disease' in Africa.

- Viral diseases in crops currently amount to about 60 billion dollars per year globally.

Viruses and Animals

- Sporadic outbreaks of viral disease in domestic animals, for example, visicular stomatitis virus in cattle and avian influenza in chicken.

- The foot-and-mouth disease in cattle is caused by an aggressive and virulent virus.

- Rabies often affects wild animals populations. It poses real threats to domestic animals and through them, occasionally, to humans.

The Origins of Viruses

- There is no geological record of viruses.

- Virus do not form fossils in any currently useful sense.

- There is ample genetic evidence that the association between viruses and their hosts is as ancient as the origin of the hosts themselves.

- Retroviruses integrate their genome into the cell they infect, and if this cell happens to be germ line, the viral genome can be maintained essentially forever.

- Analysis of the sequence relationship between various retroviruses found in mammalian genomes demonstrates integration of some types before major groups of mammals diverged.

The geological record can not provide evidence of when or how viruses originated. Genetics, however, offers some clues:

1. Viruses do not encode genes for ribosomal proteins or genetic evidence of relicts of such genes.

2. Viruses do not contain genetic evidence of ever having encoded enzymes involved in energy metabolism.

3. This finding contrast with eucaryotic organelles, mitochondria and chloroplasts, which derived from free-living organisms.

4. The reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme encoded by retroviruses, is related to an eucaryotic enzyme involved in reduplicating the telomeric ends of chromosomes upon cell division.

On the Origins of Viruses

Because viruses can not replicate without a host cell, it is likely that viruses were not present before primitive cells evolved

- One hypothesis proposes that viruses and cellular organisms evolved together, with both viruses and cells originating from self-replicating molecules present in the pre-cellular world.

- Another idea is that viruses were once cells that lost all cell functions, retaining only that information to replicate themselves using another cell's metabolic machinery.

- Others propose that viruses evolved from plasmids, the independently replicating DNA molecules found in bacteria.

Theories

There are three main theories:

- Viruses originated in the primordial soup and co-evolved with the more complex life forms

- Viruses evolved from free-living organisms that invaded other life forms and gradually lost functions - also known as retrograde evolution.

- Viruses are 'escaped' nucleic acid no longer under control of the cell - also known as the escaped gene theory.

The great variety of viruses present in the living world affirm that they originated independently many, many times during evolution.

Viruses also originated from other viruses by mutation.

The Co-Evolution Theory Has Few Supporters

- The earliest self-replicating genetic system was probably composed of RNA.

- RNA can promote RNA polymerization, although this would be a slow process and proteins present in the primordial soup may have become promoters of RNA replication.

- The DNA template is more much effective and originated early in evolution.

- RNA then became the messenger between the DNA template and protein synthesis. Thus the genetic code came into being and permitted orderly replication.

- Gradually the early replicative forms gained in complexity and became encased in a lipid sac separating its metabolic machinery from the environment. This may have been the ancestor of the pregenote and later the Archae and Eubacteria.

- Another replicative form may have retained simplicity and may have been composed mainly of self-replicating RNA surrounded by a protein coat. This entity was the forerunner of the virus and evolved to a dependence for duplication on its ability to invade and take over the genome of the host.

- Thus, there was co-evolution of the bacterium and virus.

- This theory at least can offer an explanation for the evolution of viruses with genomic RNA.

The Theory of Retrogade (Regressive) Evolution

- Viruses originated as free-living or parasitic microorganisms. This is based on the assumption that a bacterium gradually lost biosynthetic capacity and genetic information.

- Eventually the bacterium evolved to nothing more than a group of genes known now as a virus.

- Before eucaryotic cells existed, there was bacterial life. Predators such as Bdellovibrio may have existed.

- An intracellular parasitic microorganism could have become more and more dependent on the host cell for metabolites, and lost of much of its genetic information could occur without dire consequence. It only retained the ability to replicate nucleic acids and some mechanism for traveling cell to cell.

- Bacteria that potentially could regress to the viral state can be thought of Rickettsia and Chlamydia (intracellular parasites that have lost much of biosynthetic capacity, have no cell wall and can not live outside host cells).

- Bacterial origin would be more likely for complex viruses such as the poxviruses, but their genetic information differs so markedly from that in bacteria that this theory has little support.

- The absence of any life form between intracellular bacterial pathogens and viruses is also cited as a major concern.

- It is difficult to explain how RNA viruses came into existence through loss of genetic information.

The "Escaped" Gene Theory Has Considerable Support

- It proposes that pieces of host-cell RNA or DNA gained independence from cellular control and escaped from the cell.

- Cells replicate DNA by initiating replication at a specific site called the initiation site.

- A virus that could recognize nucleotide sequences at sites other than the start site and that carried the proper polymerase could have the capacity to produce RNA or DNA without interference from normal control mechanism.

- The origin of virus may have been with episomes (plasmids) or transposons.

- There is one type of transposon that directs the assembly of an RNA copy of its own DNA. This transposon can use this mRNA to synthesize DNA via RT. This copy may be inserted into the chromosome.

- The DNA of the transposon carries a gene for synthesis of the RT, and transposon elements with such properties have some similarity to retroviruses.

- Analysis of nucleotide sequences in viruses indicates that they are quite equivalent to specific sequences in the host cell.

A Current Model Places Virus Origin in the Cells they Infect

- Mechanisms of gene transposition in cells suggest that:.

- Retroviruses may have originated as types of retrotransposons (circular movable genetic elements).

- Some plant viruses may have arisen as the result of gene capture by the self-replicating DNA molecules seen in some plants.

- Others may have arisen by more bizarre mechanisms.

A major complication to a complete and satisfying scheme is that there may be a single and common origin, and viruses may appear and disappear continually in the biosphere.

Viruses do not Have a Common Origin

- If a given virus is derived from a specific cellular genetic element or elements, this speaks only to that virus and not of others.

- Even if the origin of a particular virus were rigorously established or observed in the lab, there would be no particular evidence that other related viruses had similar origins.

- It is probably not very useful to spend great efforts to be more definitive about viral origins beyond their functional relationship to the cell and organism they infect.

Viruses do not grow, metabolize small molecules for energy. They only 'live' when in active process of infecting and replicating in the cell. The study of these processes, then, must tell as much about the cell and the organism as it does the virus.